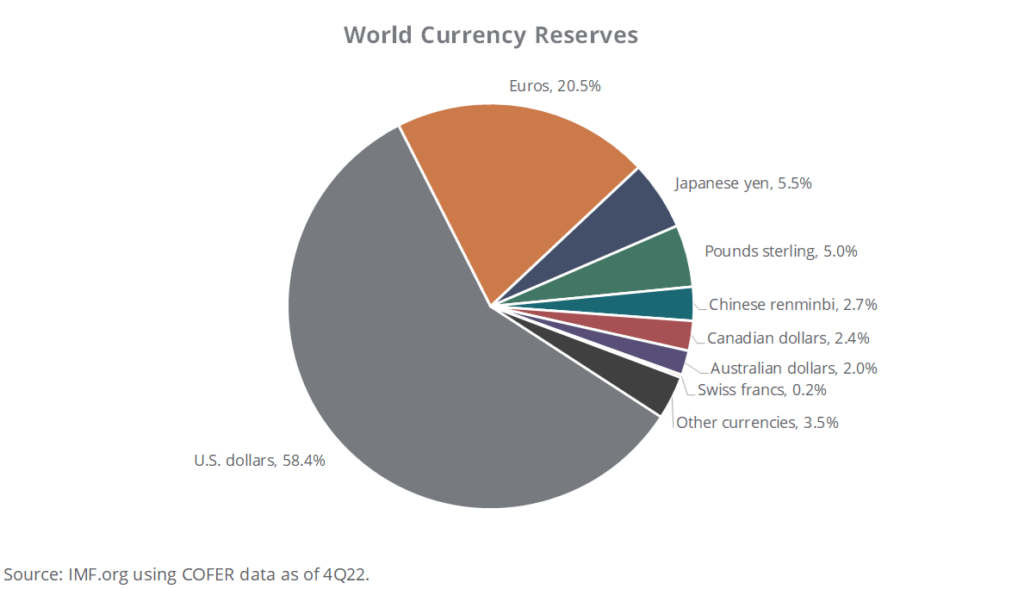

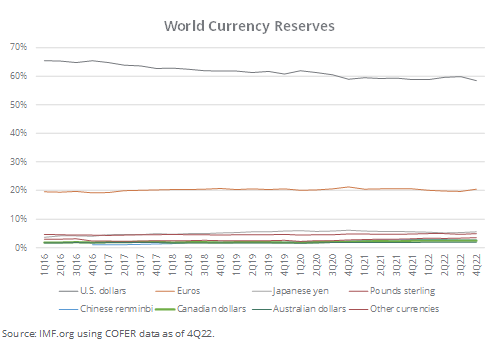

The U.S. dollar replaced the British pound as the world’s reserve currency and the primary medium to buy and sell goods across the globe after World War II. Still, the dollar’s share of official currency reserves fell to a 20-year low of 58% in the fourth quarter of 2022, down from about 78% at the turn of the century, according to International Monetary Fund data.

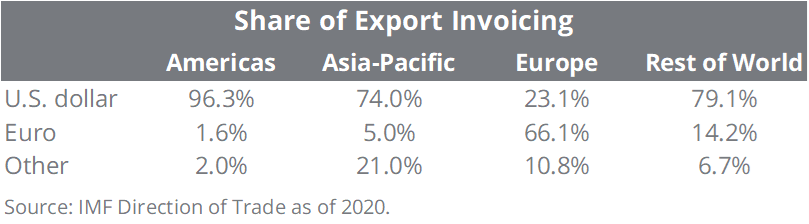

Because international trade is mainly denominated in U.S. dollars, the United States benefits from vast economic advantages: U.S. companies and consumers are generally less likely than their international peers to face fluctuating exchange rates and transaction costs. Strong global demand for dollar-denominated U.S. securities — stocks, real estate, and Treasury bonds — has allowed the U.S. government to borrow at relatively cheaper rates to fund its spending needs. The dollar’s role allows the United States to run trade deficits for extended periods, as other countries need to accumulate dollars for international transactions. However, if these imbalances become unsustainable, it could lead to a loss of confidence in the U.S. dollar.

Recently, worries have also risen amid geopolitical tensions that may bolster other currencies, such as the euro, the Chinese renminbi or even a proposed common currency among the so-called BRICS nations of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. The invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and purposeful isolation of Russia from the global trade and currency networks has led China to strategically rethink their dependence on the U.S. dollar going forward. In a way, the more the U.S. and the West push for sanctions on certain countries, the more motivated those sanctioned countries will be to establish direct trading agreements not involving the U.S. dollar.

We have seen recent contracts, especially in countries exporting commodities to China, that are being paid in local currencies such as the Brazil real or Argentina peso. As reported in Barron’s last month, Bangladesh paid Russia for a nuclear power plant in Russian ruble, and China signed a commercial contract for a delivery of liquefied natural gas from a French company in Chinese yuan.

“De-dollarization” has been a topic of discussion for at least the last 20 years. The dollar’s share of reserve currencies has gradually declined as foreign central banks have diversified. Increased competition from other currencies —including crypto currencies to a much smaller extent — could hurt demand for the U.S. dollar. However, the U.S. dollar’s incumbent role in the global economy is unlikely to be seriously challenged any time soon for several reasons. About 88% of all global foreign-exchange transactions, even those not involving U.S. companies, are in dollars according to the most recent data from the Bank for International Settlements.

According to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), the U.S. dollar was the most used currency on its global payment system, accounting for 41.7% of payments, followed closely by the euro. By comparison, the Chinese yuan was used in 2.4% of SWIFT payments, despite China accounting for a relatively larger percentage of global trade. What’s more, according to the Brookings Institution, more than 65 countries peg their currency to the U.S. dollar.

The U.S. dollar is also viewed as a reliable “store of value” and a safe-haven currency, meaning that investors often flock to it during times of economic uncertainty. The United States also benefits from a stable political system, a network of deep and reliable financial institutions, and a well-established system of property rights and contracts that makes it a safe and reliable place to do business.

While a few currencies have been discussed as potential competitors to the U.S. dollar, there is no viable alternative — at least, not yet. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, there is an inadequate supply of high-quality, euro-denominated assets that international investors and central banks can use as a store of value, and no eurozone-wide “safe” government-backed asset. China’s renminbi account for a very small portion of foreign exchange reserves, and Chinese policymakers’ control over the exchange rate makes it unlikely to quickly gain traction. Gold is expensive to move and store, thus making it less than ideal as an everyday medium of exchange.

A BRICS common currency is still hypothetical. These nations may find it challenging to coordinate across central banks and could ultimately prove unwilling to exchange their U.S. dollar reliance for a potentially volatile currency that could struggle to achieve broader adoption and introduce political instability.

Finally, geopolitical strategist Peter Zeihan recently mentioned Saudi Arabia as one interesting country to pay attention to. While the Saudis may be motivated by the current geopolitical and military landscapes in the United States and China, their energy exports bring enormous currency reserves that need to be diversified.

In April, India and Malaysia announced a new mechanism to conduct bilateral trade in rupees. Just this past May, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations agreed to increase the use of member currencies for regional trade and investment, including South Korea and Indonesia signing an accord to promote direct exchanges of the won and rupiah.

Our deglobalization theme should lead to more regional trading spheres, and we should expect that several major currencies will emerge — for example, the euro in Europe, the yuan in Asia and the U.S. dollar in the Americas — but it would likely take many decades to displace the dollar as the reserve currency of the world.

Disclaimer

The content in this article is provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as recommendations, financial planning advice, or advice about health. We encourage you to seek personalized advice from qualified professionals regarding all health and personal finance issues.